The most precious thing I own was made for me by my mother, Margaret Hodges Warren.

I have no memory of how our family became so interested in music, because I was too young. The story has it that my older sister Ursula desperately wanted to play the violin, but the family was already quite involved with horses and 4-H and camping and gardening, and so my parents did not encourage her. She made herself a crude instrument out of a cigar box, and then the local violin teacher, Gesa Fiedler (sister-in-law to Max Fiedler, conductor of the Boston Symphony), took pity and gave her a violin and lessons.

Soon all 5 of us started playing recorders. I do remember serenading friends with Christmas carols when I was 3 1/2; as the youngest, I played the smallest recorder and thus the melody. It may have been that Christmas that my parents gave each other instruments: a cello for my father, flute for my mother. After a few months of frustration, they traded. My father found the cello awkward, and blowing the flute made my mother dizzy.

When I was 6 we lived in Stuttgart, Germany, for one year. By then we were all taking string instrument lessons. My father and brother David learned viola, Ursula and I learned violin, and my mother cello. That same year Urs started oboe lessons, the beginning of her lifelong career as oboist and oboe teacher.

As a family we formed a string quintet, and this opened to us a large repertory of Baroque and Classical music. Because we provided a healthy balance of string instruments, we were a welcome addition to the local civic orchestra wherever we lived. This would not have been the case had we all played tuba — no orchestra needs 5 tubas!

There were years of lessons. We were all given piano lessons — I never cared for it. David played clarinet for several years in grade school. Urs became more serious about the oboe. Later I studied classical guitar. My father played flute in several orchestras, and my mother stuck with cello. Whenever we travelled, we found other musical families to socialize with — many Saturdays were spent playing music with friends in the States as well as in Germany.

=String instruments need maintenance. At first it was bow rehairing — each of us needed this service on a regular basis, there were 5 of us, and it was expensive. Never one to pay someone else to do something she could learn to do herself, my mother taught herself to rehair bows. Then she started to do simple repairs. Fast forward many years, and she became a violinmaker.

Let’s go back to the beginning of my mother’s story. Born into a wealthy family in Reading, Pennsylvania that lost everything in the Depression, she was frugal and resourceful, independent, modest — even bashful — kind, private, determined, and family-oriented. Her home life was somewhat checkered, and she followed her father to Heidelberg, Germany, when she was 15. Although she spent a few years at the University of Louisville, she neglected to complete the requirements for a college diploma, opting instead to go straight for a Ph.D. in Art History, which she earned when she was 21. Completely on her own during the summers, she taught English to the children of a wealthy French family one year, and to the children of an Italian family the next. Her university classes and her dissertation were in German. By the time she was 21, she was fluent in English, German, French, and Italian.

Having grown up in unstable times, she wanted nothing more than stability and a strong family life. She met my father at Heidelberg University, where he earned his doctorate in political science. He had grown up in Brooklyn, New York. He loved music as a child, sang in the Trinity Boys’ Choir, and sang a solo “Mother’s Song” on the radio each Sunday morning. My parents shared a love of classical music and all things intellectual. They left Germany in 1937, hurried along by Hitler’s growing influence in the country. After a few years in New York City and on Long Island, they moved upstate to Alfred, New York, for my father’s teaching position, and this is where they began to raise a family.

World War II intervened.

The family settled into the “happy days” of the 1950s. We owned a small farm, raised chickens, milked cows, and rode horses and ponies. My mother taught horseback riding to the children in the town. My sister and brother participated in 4-H. My father taught. My mother raised nearly all our food and made most of our clothes. I was born. Life was good. And somewhere in there, Urs wanted a violin.

And that brings us full circle, back to my mother’s need to rehair bows and make simple repairs. After working on our instruments, she started repairing other people’s instruments, and then all of the string instruments for local schools, and her interest in building started to grow.

Instrument Building Begins

Her knowledge of foreign languages came in handy when my mother started building instruments. With no one to guide her, she relied on original manuscripts written by the German (Mittenwald school), French (Mirecourt school) and Italian (Cremona school, e.g. Stradivarius) masters.

Imagine building such a sophisticated instrument as a violin. The top, back, and scroll (which includes the neck) are carved out of large blocks of wood. The sides are bent, using heat and moisture, into the curves required to match the top and back. Most of the instrument is held together with hide glue (made from animal hides), used because it is weaker than the wood. Why? So that, in the case of stress in the instrument’s structure, the seams give way to protect the wood from splitting. It is much easier and better to reglue a seam than to repair a split.

One special detail on instruments in the violin family is the purfling, a 3-ply (ebony/ivory/ebony) inlay just inside the edges of the top and back plates. You might assume that it is only decorative, but it serves a function. It is inlaid right where the sides are glued to the plates; by making the wood at that joint thinner, the wood is able to vibrate more easily. On very cheap violins, you may find that the purfling has been drawn on.

My Violin is Born

My mother built a violin for Urs. Then she built a viola and a 5-string (combination violin and viola) for David. I knew I was next. Even though her instruments were excellent, I pleaded with my father to discourage her from building an instrument for me — by then I had earned the title of Master Fiddler at the Fiddler’s Grove Festival, the longest continuously running fiddle contest in the country. And, well, “I’ll choose my own instrument thank you.”

After I started winning contests, my parents decided to drive to North Carolina from their home in New York to see what all the fuss was about. My mother ran fiddle maintenance workshops at Fiddler’s Grove for many years, doing simple repairs and teaching musicians how properly to care for their instruments. Since she didn’t play violin herself, and because I only saw them a few times a year, she often brought violins with her for me to try, violins she had acquired at flea markets and repaired.

One of the violins she brought in 1986 played beautifully. It was well balanced across all of the strings. It had a deep throaty sound at the low end. I couldn’t put it down. I played it for hours. Then she told me to look inside, at the inscription. Instead of the fake Stradivarius paper labels inside many violins, mine is inscribed in my mother’s hand:

made especially for

M. Robin Warren

by Margaret H. Warren

Andover, NY

February 1986

Since 1986 I have never performed on another instrument.

Brian Clancey Arrives on the Scene

Years passed. The highlight of my year was the annual trip to Fiddler’s Grove in May. I would practice for a few weeks beforehand to prepare for performance, but once I returned to New Hampshire, I would lose interest again because I had no one to play with. And so most of the year the violin sat alone in its case.

I longed for a musical partner, someone who would put up with my quirks (musical and otherwise), play fantastic guitar in a multitude of styles, and yet willingly play backup behind me. In 1998 Brian Clancey arrived in my life and met all of the criteria. Believe it or not, he was playing a guitar made for him by his father!

Brian grew up in a musical family, the youngest of 5 children. The Clancey household had more instruments than toys, and they listened to the widest variety of music imaginable. There is a movie of Brian as a toddler, rocking his playpen to wriggle it closer to the phonograph — at that age he already knew where the music came from and how much it meant to him. I have seen photos of him playing banjo, piano, trombone, clarinet, baritone horn, mandolin, accordion, hammer dulcimer, ukulele, flageolet, hurdy-gurdy, autoharp, Renaissance lute, and of course guitar. He can also make music on plumbing pipes and chair spindles…

The family played Folk Masses in church and entertained in rest homes. His father Herb lulled the children to sleep each night with his funny songs, ukulele, guitar, and chromatic harmonica.

In his spare time, Herb Clancey built instruments in his luthier shop in the basement, in part to escape the bustle of multiple children playing upstairs. Over the years he built guitars of all types (resophonic, classical, Spanish, cowboy, bluegrass) as well as violins and mandolins and dulcimers. He built several medieval and Renaissance instruments as well — a hurdy-gurdy, a shawm, gambas, multiple lutes, a fidel, a rebec.

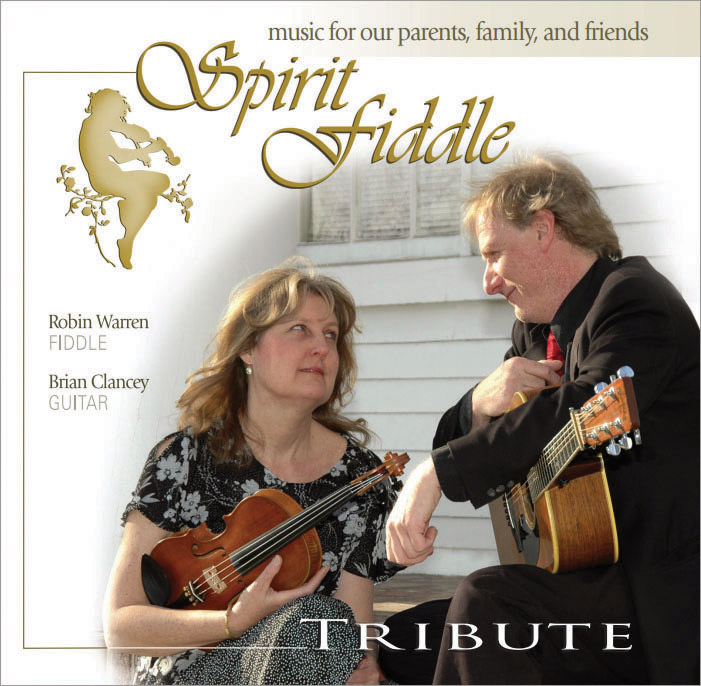

With backgrounds that were similar in many ways (and quite different in others), and an intense shared love of music, Brian and I started playing and performing together. Our duo, formed in 1999, is named Spirit Fiddle. In the past 20+ years we have given 1000s of concerts in the United States and Canada, and we have recorded 7 CDs.

Endlessly I am asked “What is the difference between a violin and a fiddle?”

My answer:

None. Same instrument. Same bow. Different playing technique and style.

And audience.

Brian’s answer:

You don’t spill hot sauce on a violin.

The Tools of the Craft

Many of the tools an instrument builder needs are unique to the trade. My mother made many of the tools she needed, and she was a master at sharpening chisels, knives, gouges, scrapers, and other blades. She passed away in 2004. When we closed her shop, many of her tools were given to the only person we knew who would appreciate them — Brian’s father, who also made his own tools.

When Brian’s father passed away in 2013, we discovered my mother’s tools right on his workbench — he had been using them every day.

My parents are gone. Brian’s parents are as well. They passed along to us many gifts and abilities, including our love of music and the instruments we play.

A person who builds violins, violas, cellos, and bass viols is called a violin maker. A person who builds guitars and mandolins is called a luthier. They tend not to be the same person, and they require different skills and tools. The top, back, and scroll of a violin are carved, whereas most of the wood a luthier uses is flat or bent into shape. Herb’s mother thought he had changed religions when she heard he was a luthier.