The USS Block Island (CVE-21), a “baby flattop” aircraft carrier, was struck by 3 torpedoes in the middle of the night of May 29, 1944. Once the order to abandon ship was given, Warren was responsible for locating and securing all classified communications in a safe, in the pitch dark — the power had gone out — before he could leave the sinking ship. The story continues in his words …

We paddled to the destroyer Ahrens, which was standing by taking on survivors from the ship. On the way, we heard a loud roar and saw that the destroyer escort Barr had its fan-tail (the back of the ship) blown off by a torpedo. At that distance from the destroyer — a mile or so — the impact through the water was minimal. Also, at some point, the destroyer escort Elmore succeeded in sinking the U-Boat with a depth charge. I came to believe that the warning I had received at Harvard was somewhat exaggerated, except perhaps at the closest distances.

When we reached the Ahrens, we climbed aboard on cargo nets. Officers were ushered into the cramped “officers country” of the ship, consisting of a small ward room (dining room) and a few individual bunk rooms. Enlisted men were taken to the crew’s quarters. We were all dripping wet with oil and water — an ungodly mess.

While climbing up the cargo net, I noticed Delver Dally, my close friend from the ship, who was just emerging from the water. Being a strong swimmer, he had swum unaided the whole distance to the Ahrens. I noticed that he did not have his life-belt on. “How come?” I asked him. He had given it to an enlisted man who didn’t have one. I could not but think of the contrast between this fine man and the overbearing officer who had complacently taken two life-belts.

There had been about a thousand officers and men on the Block Island, including the flight crews. By some miracle, none of the three torpedoes had struck the high octane aviation fuel tanks or the compartments where the ship’s munitions and bombs, torpedoes, and depth charges were stored. Out of the more than a thousand on board, only six had been killed. In addition, several planes that were in the air could not make it to a landing field and went down at sea. [2 pilots were rescued, 4 perished.]

Some 300 of the Block Island crew made it to the destroyer escort Paine. 73 officers and 601 enlisted men were taken aboard the Ahrens, crowding her extremely. From the deck, we watched as the old Block Island listed more and more in the water and finally sank stern first into the sea. The Ahrens was still at “general quarters,” and remained so during the night as the battered task group searched the area for further submarines. Next morning, we headed off towards Casablanca.

Our emotions were mixed. There was sadness to see this ship that had served so gallantly in war against the German U-Boats going down to the ocean floor — itself a U-Boat victim. At the same time, we were thankful to have been saved and grateful that only a few men had paid the final price. There was also still the sense of danger, reinforced by the damage to the torpedoed destroyer.

There were so many of us in officers country that there was not room for all of us to sit or lie down on the deck. Some of us had to remain standing. As night fell, different ones occupied the bunks, two at a time, but of course they could accommodate only a small number of the officers who had come aboard from the Block island. The situation in the crew’s quarters was similar.

The following morning many of us were out on deck when a B-24 (Liberator) bomber came into sight and flew parallel to us for a while as we cruised in the direction of Casablanca. After the tense night at general quarters this friendly plane was such a welcome sight that all hands ran over to the starboard side, off which the B-24 was flying.

The destroyer began to list! There were so many of us on this little tin can, as destroyers were affectionately called in the Navy, that orders had to be given for us to equalize the load on the ship.

It took two or three days to reach Casablanca. During this time I wrote this brief description of my own experience during the torpedoing.

We were billeted comfortably in Casablanca and issued new army clothing. We remained there for ten days or so until a carrier returning to the U.S. took us back. While in Casablanca, on June 6, I remember getting the French/English newspaper and reading the dramatic news of D-Day and the invasion of Europe.

All the crew of the Block Island were given a month’s “survivors leave” and then we were reassembled as an intact crew on the West coast to put in commission another carrier to engage the Japanese. The new carrier’s name: the Block Island.

Roland’s wife Margaret knew nothing of the sinking until neighbors started showing up at her door with casseroles and hugs. There had been a one line report of the sinking in the paper, with no additional information, and Navy wives knew that the previous aircraft carrier, the Liscome Bay, had gone down with no survivors. It was several days before word came that most of the crew had survived. Such was the life of a serviceman’s wife during World War II.

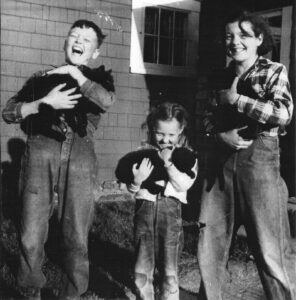

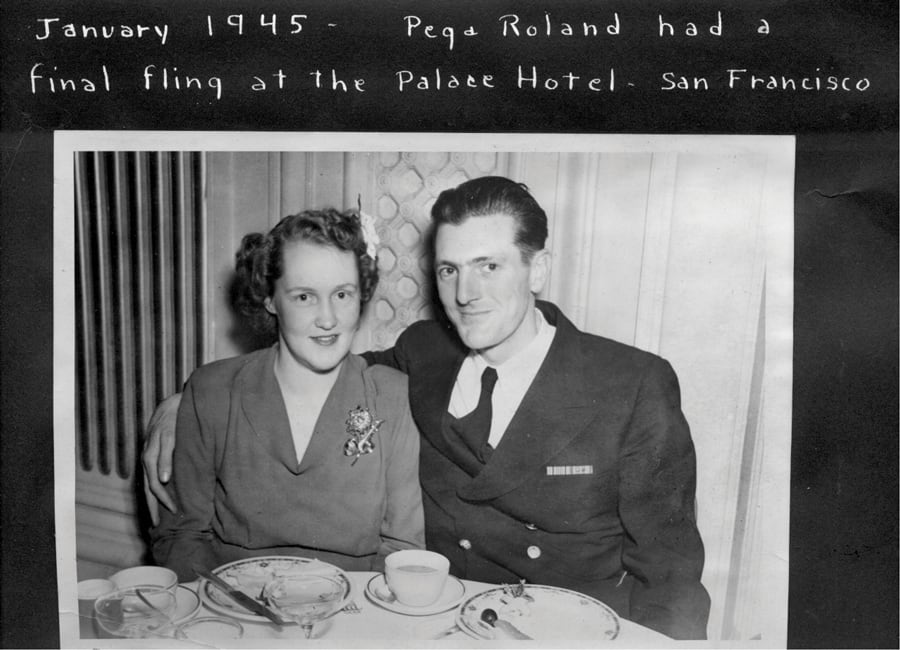

Roland Warren returned to his wife Margaret (Peg) and two toddlers in Alfred, New York, for his survivor’s leave. Determined to spend as much time together as possible, the family drove across the country for the launching of the new Block Island. After a sad parting in San Francisco, Peg used their limited gas and tire rations to drive back to Alfred with their two very small children.

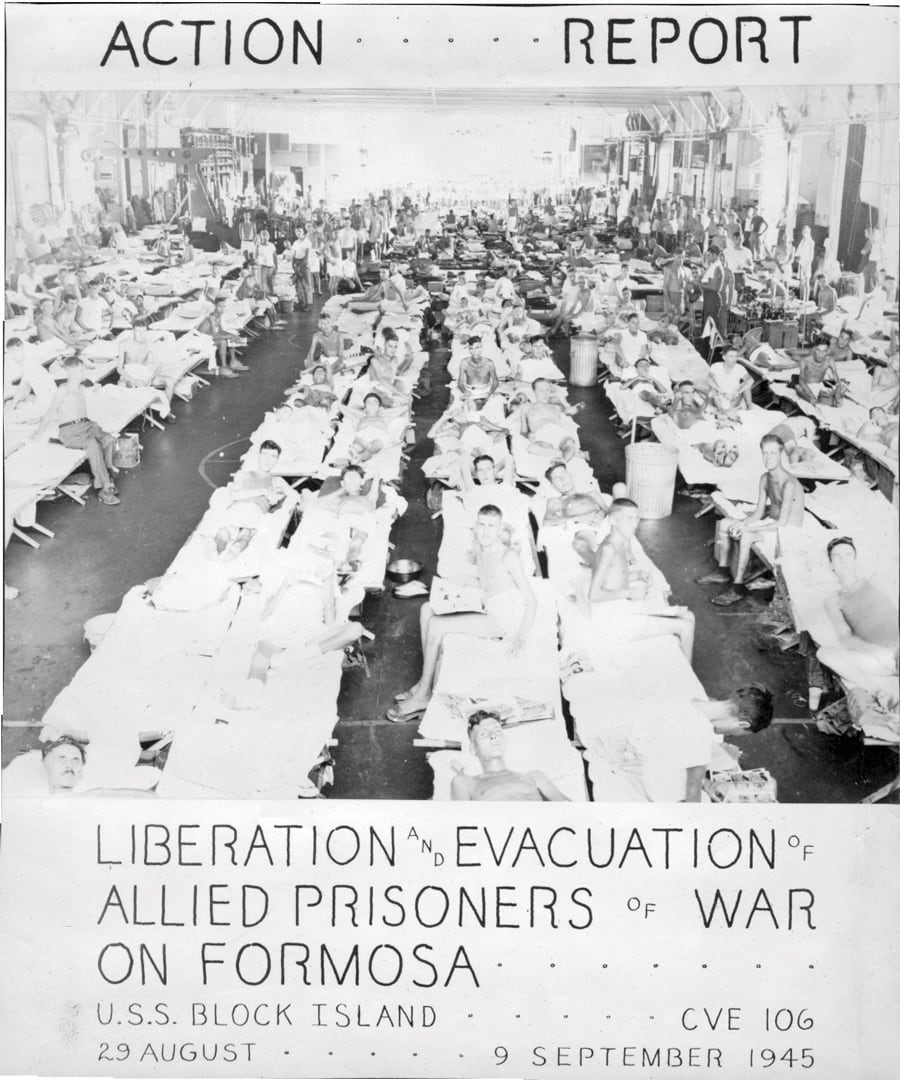

The new Block Island, USS Block Island (CVE-106), set sail for Hawaii in March of 1945, and then joined the 7th Fleet in Ulithi in preparation for the invasion of Okinawa. She was involved in several battles in the Pacific and took part in the evacuation of Allied prisoners of war from Formosa. After the war ended, she returned to the United States, where Roland was able to disembark in San Diego and make it home to Alfred in time for Christmas. Many years later a 3rd child named Robin joined the family …

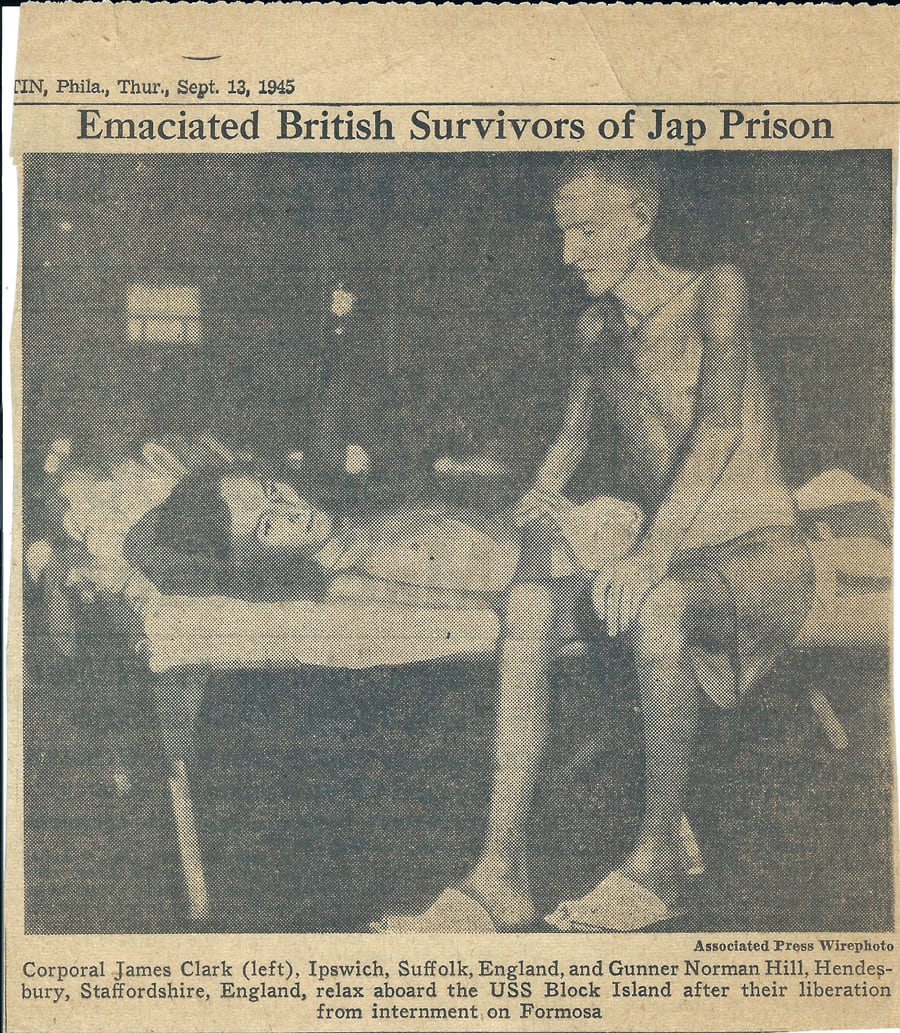

Two British survivors relaxing on board the Block Island after their evacuation from POW camps on Formosa.

Allied Prisoners of War aboard the USS Block Island after their liberation and evacuation from Formosa.

Peg and Roland had a final fling at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco before the new Block Island set sail in the Pacific.