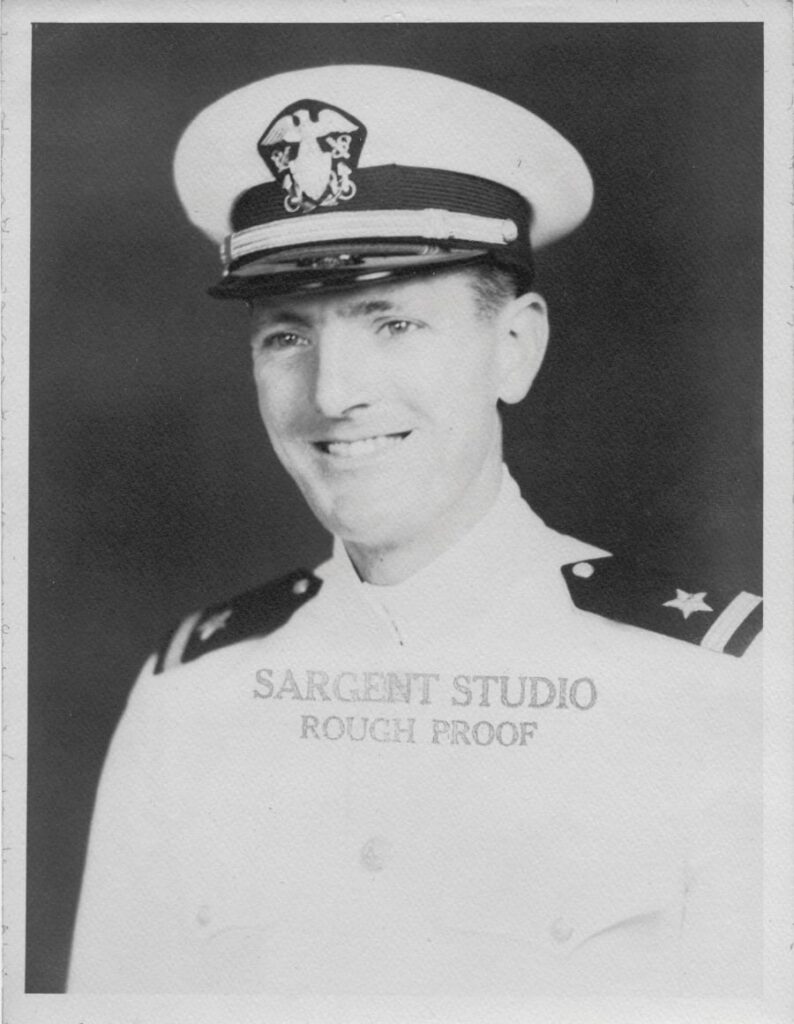

This is Part Two of a first person account of the sinking of the USS Block Island (CVE-21), a “baby flattop” aircraft carrier, by a German U-boat in the battle of the Atlantic during World War II. Part One described Warren’s duties as Navy Communications Officer, and ended with the first 2 torpedoes to hit the Block Island. Warren was relaxing in his living quarters, at night, when, in his own words …

BOOM, and then another BOOM!

We hot-footed it out of there and up the ladders to our battle stations. Halfway to the Communications Office, the clanging sound of “general quarters” reverberated throughout the ship. I had been in my slippers, and I noticed that one of them had slipped off on the way. Never mind that.

As soon as I reached the Communications Office, I started gathering the classified documents for storage in the safe, checking them off my list.

One entered the Com Office through the radio shack, where the ship’s powerful transmitters and receivers were located, and where crew members copied the Morse code messages and determined which messages were for our ship. These were then carried into the coding room for “breaking” with special decoding equipment. It was the duty of the communications watch officer to decode these messages and route them throughout the ship to the officers who must see and initial them. He had to indicate also which officers were to receive the message for “action,”, and which for “information” only.

Bill Brault, the communications watch officer then on duty, was already starting to stow the publications. We both gathered the necessary publications from the radio shack and assembled the various ones in the coding room, stuffing them into the safe. We had nearly finished the job, when —

BOOM!

A third torpedo hit the ship. This one really rocked the ship; it was so strong that all the publications stored so carefully on the shelves in the still open safe came tumbling out onto the deck. The ship’s power was knocked out and the lights went off. At about this time Ensign Daly, one of my roommates and my closest friend — also in communications — came by and said the order had been given to “stand by to abandon ship.” Until that fateful moment we knew only that the ship had been torpedoed — and might explode any minute — but we were not certain how bad the damage was. After the Liscomb Bay disaster, we had a sense that we were operating on borrowed time.

Our situation in the coding room was problematic. It was now pitch dark in there, and the numerous publications still had to be re-packed into the safe before we could leave. I grabbed the battle light, only to find that the battery was dead. How ironic, I thought, as I recalled the many hours I had spent in that room decoding messages and facing that battle lantern fastened to the bulkhead in front of me, making a mental note of its location in case I ever needed it. Now I needed it and it was useless.

This was one time when a little bit of common-sense planning on my part paid off. On these anti-submarine missions to and from Casablanca, I always carried in my left-hand shirt pocket a small survival kit which I had put together myself. It consisted of a small steel mirror, a pencil, a little sample box of two cigarettes, a folder of matches, and a pen flashlight — all stuffed inside a condom which was then fastened with a rubber band, making the whole small package waterproof. Now, I broke out the pen flashlight and by its light we hurriedly stuffed all the publications back into the safe, locked it, and beat it out of there, closing both doors behind us.

I ran up to the flight deck and found that most of the crew were already either in the water or going over the side on lines and cargo nets. I ran into one of the other communications officers, a rather gruff, aggressive type who was my superior in rank.

“About time to hit the water,” he called.

“Right,” I said as I headed toward a ladder to go to my abandon ship station just forward of the hangar deck housing. But I shook my head in amazement as I did so, for this pompous officer was wearing not only his inflatable life-belt but also an inflatable aviator’s life jacket that he had somehow gotten hold of. He looked a disgusting sight.

On the well deck, while I was busy supervising the cutting away of a fouled raft, Charles Brown, officers mess attendant, came up to me excitedly and said what I thought to be that he was unable to get to his abandon ship station aft. I told him in that case to over the side right here and now, since the word had already been passed to abandon ship, and men were already going over the side on lines, many of them already in the water with rafts. Charlie replied, “No sir, I didn’t mean myself. I can get over alright. But there’s a man back here with a broken leg. Can you help us get him over?” This was what he had said the first time, but I had not understood him. Now I saw the man, an officers mess steward. A couple of the mess boys went over the side and got a raft. We tied a line around the mess steward and lowered him into the water. Then I had to tell the others to go over, for they were still looking around for things to do to help, even though this was long after the order to go over the side had been given.

The rafts were of the familiar “doughnut” type — an oblong frame rounded at the corners, from which was suspended by ropes a floor that rode perhaps two-and-a-half feet below the surface. There were several rafts in the water when I went over the side. I swam comfortably with my inflated life-belt, and was about to reach one of the nearly full rafts when I heard behind me someone crying out for help. I turned so I could see the man. He was wearing a large kapok life jacket, but apparently was so panicked that he was thrashing about with his arms and taking water into his mouth, all the while crying out frantically.

I was mortified. The water was full of oil near the ship. Two things made me fearful. I recalled that the Liscomb Bay had gone down in sixty seconds, and there was no way for me to know whether the Block Island would likewise sink, dragging with her everything within a wide range. The other cause of fear was a warning given to us back at Harvard by one of the experienced Navy instructors, that if you are in the water when a depth charge goes off, the impact can tear your insides apart.

There was nothing I could do but swim back towards the carrier some forty or fifty feet to where he was, and tow him to safety. I swam back to the man, calmed him down, and towed him to a life raft, whose occupants hauled us both aboard.

to be continued …