Every family passes stories down to the children and grandchildren. Some are unique to the family, and others tell of historical events that affected an entire generation. My father wrote most of what you will read below a few days after the event, and he added some explanatory details later. This article is in 3 parts, and this month we publish Part One. Many many young Americans were lost during World War II. Fortunately for me, my father was not one of them.

– Robin Warren

“You are going to be the custodian of publications.” Lt. Commander Gilman, the communications officer, addressed me in a friendly, informal way, but his voice was firm.

I winced. “But I don’t know anything about that job. I was trained as a visual signal officer.”

“You’ll have to learn quickly. Lt. Putnam is being relieved to take on other duties, so you will be in charge of classified publications.”

I thought back to what I had been told by the seasoned instructor at the Harvard Naval Communications School where I had received my training the preceding months: “Do your best not to be the custodian of publications. In case of trouble, you’ll be the last one off the ship. And then, if you get off, you’ll be filling out forms the rest of your life.”

Having just been assigned to CVE 21, the small aircraft carrier “Block Island,” and having just come aboard, I was hardly in a position to demur, much as I would have liked to! The custodian of publications is in charge of keeping track of all classified (more or less secret — some highly secret) publications, knowing where they are on the ship at all times, and destroying them when they become outdated. The record keeping is fairly substantial — and of course, you don’t dare lose one of the darned things. In case the ship should sink, all publications must be secured either in weighted mailbags thrown over in deep water, or locked in the safe of the sinking ship, so that they could not somehow float to the surface and be captured by an enemy. Once on shore, you would need to give an accounting of the publications.

I had little stomach for this position. As a matter of fact, the assignment to a carrier had come at a most inauspicious time. It was only two or three days since the announcement that the escort aircraft carrier Liscomb Bay had been sunk in action in the Pacific and had gone down some sixty seconds after being hit. Four other carriers had been sunk in the Pacific: the Lexington, the Yorktown, the Wasp, and the Hornet.

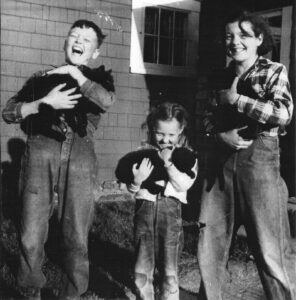

I had volunteered for the Naval Reserve primarily because it was possible to obtain officer status to begin with, whereas in the other services I would have had to take my chances. With a wife and little girl at home and another child on the way, we could use the somewhat higher salary. There were other advantages as well.

Because I had spent two years in Germany and knew the language well, I had applied for Naval Intelligence, but such an assignment must have seemed too logical for the Navy. Instead, they put me in communications and sent me off to the training facility at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

However, my knowledge of German was taken into account on the Block Island and I was made Prisoner of War Officer — in case we should ever take any German prisoners.

How would an aircraft carrier come to take German prisoners? The Block Island was doing antisubmarine duty in the Atlantic, plodding back and forth between Norfolk, Virginia and Casablanca, escorted by four destroyers or the smaller destroyer escorts. A carrier itself was hardly a match for German U-Boats, and was not designed to be, but its planes and the accompanying destroyers could be highly effective against submarines. Of course, the Block Island would never taken a German prisoner; after all, when a submarine is sunk, you don’t expect to see survivors.

Or do you? On our first trip out of Norfolk, the task group had been pursuing a submarine, which for some reason surfaced and began shooting it out with a much more powerful destroyer. The destroyer sank the submarine and captured a number of the crew, whom they swung across to the Block Island on breeches buoys the following day. This was the first of several crews that were captured rather dramatically in the course of our operations during the next months.

An interesting sidelight: there was a saying in antisubmarine warfare that a ship did not get credit for a “kill” unless it came back to port with the submarine captain’s trousers tacked to the mast. There was one occasion on which the Block Island group came back not only with the submarine captain’s trousers, but with the submarine captain himself and some of his crew — and still we were credited only with a “probable.” I was the translator when our captain invited the submarine captain prisoner to dinner.

On the night of May 29, 1944, Ensign Nelson and I were sitting with our feet up on our respective bureau-desks in our living quarters (shared with four other junior officers) on D Deck, which was down below the water line. We had had a nice dinner, all things considered, and were chatting amiably. We had already been at sea some two weeks on this trip.

BOOM!

We looked at each other for a split second. That sounded ominous. We took our feet down off our desks.

BOOM! Another one …

The USS Yorktown (CV-5), an aircraft carrier like the Block Island, was commissioned in the Navy in 1937. She was prominent in the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway in the Pacific in 1942, was heavily damaged, and eventually sank. Her name lives on the USS Yorktown (CV/CVA/CVS-10) that was commissioned in 1943 and served in the Pacific Theater, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. She also was the recovery ship for the Apollo 8 space mission. Since 1975 she has been a museum ship at Patriots Point, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, and you should visit her when you are in the Charleston area!)